*Scroll to the bottom for a plain language summary

By Sama Nemat Allah

What would happen if we created spaces founded on and driven by access? Instead of viewing accessibility as an afterthought — as an extraneous or immaterial additive that invariably falls on the disabled individual to ask for — how would an academic space change if accessibility was sewn into its fabric?

Listen to the article recording here

As a disabled journalism student, I am rarely impervious to the ways both the industry and the institution paving my path to it are inaccessible to me and my kin. Media and scholarship demand an expediency that my chronic fatigue cannot provide, move at a pace my disabled body can not keep up with and speak in a language that my neurodivergency often resists. When I require support and accommodation, I have to ask — or rather plead — for it. My needs are treated as abnormal and burdensome.

This article hopes to articulate a different truth about the intersections of accessibility and academia, and will do so while presenting best practices and lessons learned from our May 2023 Between Ideals and Practices conference.

Although Canadian universities are required by law to accommodate disabled students and faculty, studies show that

disabled academics don’t feel welcomed, included or represented in scholarship. Disabled researchers and instructors, for example, are among the groups that experience the highest levels of harassment, social exclusion and unfair treatment within post-secondary institutions. And with disabled students in Ontario being nearly 24 per cent less likely to attend university at all, it too often feels like higher education environments don’t care that we’re left behind.

Born out of these experiences was my role as an accessibility coordinator for our Canadian conference focusing on the transformation of journalistic roles. We wanted to develop a blueprint for organizers and academics to shape and futurize higher education environments that are designed for everyone. Disabled people are a part of every team, every audience and every community. Once we accept this as a fact and not merely as an indeterminate possibility, access becomes core to cultivating any space, academic or otherwise.

Putting best practices into practice

Accessibility Statement: One of the first and most imperative ways to “accessibilize” a conference at an organizational level is by creating an accessibility statement. This communicates a commitment to meeting the needs of anyone accessing your organization’s physical or digital spaces. It’s important for this statement to be created and approved by everyone within your collective so it becomes the fulcrum of all content produced and decisions made. Because disability justice practices see accessibility as a dynamic and collaborative process, it’s critical you return to your statement frequently even after its creation and implementation: as your organization learns, grows and changes, so too should your commitment to bettering access standards.

As an example, take a look at JRP Canada’s accessibility statement found on the Editor’s Note page at the beginning of the magazine.

Event Registration and Accessibility: During the registration process of your conference, ensure there is a place for attendees to see what access points you offer as well as request an accessibility service. This provides organizers an opportunity to meet access needs, to apply for more funds for additional accessibility features and opens the door for communication between you and those you hope to support.

What you learn from registration should inform the creation of your accessibility guide—a one-stop shop for accessibility information for your conference or event. We drew inspiration from Tangled Art + Disability Gallery’s Cripping the Arts Access Guide. Written in plain language, these guides provide detailed information about the event space (including but not limited to the locations of nearby parking spots and airports, accessible entrances, bathrooms, elevators and stairs), as well as the event’s access points (American Sign Language interpretation, audio description, live transcription and captioning, scent-free zones, food sensitivities and relaxed rooms/presentations) and should also contain a synthesized event agenda with timings and locations. You can see an example of our guide here. Guides should be offered before the event so attendees know what to expect and can plan their experience accordingly. Also be sure to survey participants after the event to see what worked well and what didn’t.

Along with surveying them on their own accessibility requirements—like podium height, interpreters and preferred seating— be sure to provide presenters and speakers with guidance on how to make their presentations more accessible. Our team offered all presenters a slide template that outlined aesthetic (font size, colour contrast) and oratory (giving visual descriptions of themselves and images, speaking in plain language) tips to support them in making all the material disseminated at the conference accessible.

Virtual Accessibility: Always offer people the option to attend your events, seminars and conferences virtually. The ubiquity of technology, social media and virtual conferencing in and beyond the academic realm has created boundless possibilities for furthering accessibility. But when we don’t take proper advantage of those access practices, we miss out on simple ways to promote inclusion. Virtual access shows that we’ve, as disability justice artist, activist and academic Eliza Chandler puts it, “anticipated” our audience exactly as they are.

When an academic conference offers alternative options of entry using online video conferencing platforms like Zoom, for example, it can decrease barriers for international, immunocompromised, chronically ill or spoonie guests—disabled people who rely on Christine Miserandino’s Spoon Theory to explain their energy or capacity levels on a given day— to participate in the event. Zoom and other platforms’ software can also provide guests tuning in virtually or in-person with live captions, in the language of their choice.

ASL interpretation: Standardizing ASL interpretation and Communication Access Realtime Translation (CART) services for all events, online or otherwise, also ensures that d/Deaf and hard of hearing community members can have access to all content and information shared in your events. Consider whether you want ASL interpretation on-site or virtually, or whether you want event recordings to be interpreted after-the-fact.

Social media: Accessiblizing your social media presence begins at structuring your posts for a screen reader, a tool that transforms text on a computer screen or device to voice for Blind, visually impaired and low-vision users. In other words, translating a largely visual culture into a verbal one. An uploaded graphic, illustration, photograph or media should always be accompanied by alt-text or an image description that clearly and accurately gives an account of what someone would be seeing.

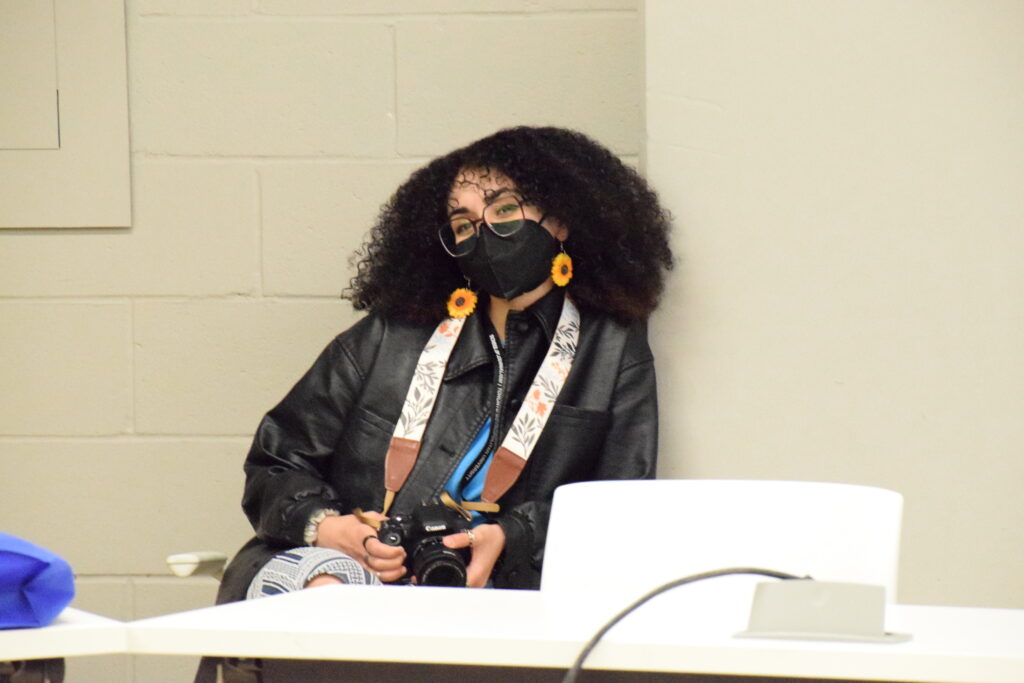

An image description allows you to navigate and translate this visual experience to your audience. It also has space for some creative interpretation from you as the translator. Some questions I ask myself when I’m writing image descriptions include: Is this image in colour or black and white? Can I carry the reader through the image’s background, middle ground and foreground? Or is it better to carry them clockwise through the image? But as an image describer, always make sure you’re in conversation with your community: are your descriptions too short or too long from them? Too abstract or too plain? Implement suggested changes that make your images more accessible.

If there are people featured in the image, it’s best practice to ask them how they’d like to be described. Is there a racialization, ethnicity, disability or gender presentation that they would like mentioned? Err on the side of a general denomination or description (simply stating the individual’s name, for example) if you’re unable to retrieve that information from them. But never make assumptions about identities and how someone would like to be perceived/described. See the description below for an example.

Image Description: A photograph of Sama Nemat Allah, a light-skin femme-presenting Egyptian individual with black curly hair and large square glasses, wearing a black leather jacket, a KN95 mask and sunflower earrings, seated leaning against a white wall. She is holding a Canon camera that’s hanging from her neck by a floral camera strap.

If your post includes a link, make sure to use a shortener like bit.ly to reduce the number of characters. Make your hashtags user-friendly by capitalizing the first letter of every word to avoid them being read as a jumbled up singular word.

Transcriptions: Provide captioning and transcriptions for all audio and video content. Using transcription tools like Otter.ai or Zoom can be great starting points for your transcripts. But with the AI’s tendency to mishear (I’ve seen “synonym” be transcribed as “sin a name”) and its inability to make notations of silences, laughter or statements said sarcastically, it’s important to allocate human resources to reviewing the text and making sure it syncs up with the audio. It’s also important to consider privacy issues and data storage practices for these types of technologies.

Plugins: You can also implement accessibility plugins in the backend of your website to allow users to increase webpage contrast, change font sizes, underline and highlight links or get rid of animations and page styling that may be distracting. Wordpress and other website builders offer a number of accessibility widget options, but others may require additional money, maintenance or coding. Make sure to incorporate a keyboard navigation system onto your website for users not using a mouse. Run your website through an accessibility checker such as the WAVE Web Accessibility Evaluation Tool to check for its compliance with accessibility standards.

Intellectual Accessibility: The academic system gives rise to language with needless complexity, referred to as opaque writing by anthropologist Victoria Clayton in a 2015 Atlantic article. It excludes and marginalizes not only those outside of the field of academia, but also those with cognitive or learning disabilities or enminded differences—like Mad-identifying folks (a reclaimed socio-politcal identity for communities whose mental states have been pathologized/criminalized, often labelled as “mentally ill” or as having “mental disorders”) or Indigenous people who identify with a decolonial experience of thinking and being. Offering research papers, studies or presentations in plain language, while unlikely to create total access, will mobilize more knowledge in a more accessible way. And a plain language communication approach done effectively stays true to an original text while concurrently relaying the vital information it houses. While there is no definitive standard for writing in plain language, using shorter sentences, opting for the most commonly used words and using an active rather than a passive voice are all tips that work in conjunction to make works more digestible. For reference, look back to the “In Summary” sections attached to the articles in this magazine, including this one.

But because the use of jargon is almost unavoidable in most academic productions, it’s best practice for academic conferences to offer printed or digital glossaries for guests to access during and after the event. Sending out a collaborative glossary spreadsheet for speakers to define/clarify important terms, jargon and concepts employed within their presentations can make for an effective, community-borne access point.

This publication in and of itself is an example of a collective measure of intellectual accessibility in motion. With a team of student reporters creating easily digestible articles of each panel, including simple language summaries, attaching QR codes when possible and in offering the magazine online, we’ve collectively translated an exclusive academic space into an inclusive tangible one.

Lessons Learned

If you’re looking to lead with access—for accessibility to be foundational to the creation of your academic event—make sure you allocate money for accessibility from the get go. ASL Interpreters, CART services, accessibility coordinators or consultants, and the creation of this type of magazine will all require funds to facilitate. And while most of the aforementioned practices can be implemented with the right time, effort and careful consideration, at the end of the day, there were a number of opportunities for access that we simply couldn’t seize because we underestimated our budget needs.

For example, with more funding, we could have had a live ASL interpretation for the panels and keynotes**. This would have required travel costs for a team of at least two interpreters, at a rate of approximately $250 each for every hour of interpretation.. Because our conference included concurrent panel sessions, to provide interpretation of the entire event we would have needed several more interpreters, amounting to more than $10,000.

Although we planned to offer an ASL interpretation video after the event that captured both the opening and closing keynote presentations, we were unable to finance it because we didn’t account for the additional costs to the provider for video editing and captioning, or realize we would need two interpreters due to the length of the video**. Asking an ASL service or organization for a quote early on in your planning process is the best course of action to ensure you’ve allocated enough money, but keep in mind that they will likely require a script or audio of the presentation before providing you with an accurate estimate, which might be difficult to get before the event. We hope to be better prepared next time to offer what should be a default part of every space and one that enriches the experiences of those that have an alternative means of communication.

Accessibility is not an isolated act, but an on-going endeavour—the more we learn about our needs and those of one another, the more we’re able to make time and space for those needs in our academia. For example, while none of the researchers we shared the “jargon” spreadsheet with were able to make additions, it was still an important space to foster and one that we hope to try creating again. It also taught us that accessibilizing cannot fall to one person, but that a joint enterprise of care requires the labour of all participating parties to truly be brought to fruition.

We saw these acts of collective access come to life in our conference. When we requested that presenters self-describe—an access point that gives blind and visually-impaired folks an idea of what someone looks like—we heard as, one after another, speakers outlined the colour and length of their hair and the details of their outfits. Many presenters used the accessible slideshow template we provided them with before the event. The webs of care and access, as transformative justice educator Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha names them in their book Care Work, were not “an unfortunate cost of having an unfortunate body” but a “collective responsibility that’s maybe even deeply joyful.”

It’s also important to remember that disabled creatives, students and scholars are experts in their own experiences so immeasurable gratitude must be given to them for carving out these spaces of interdependence and safety for themselves and one another.

At the end of the day, what accessibility asks of us is community care. What lengths are we willing to go to to ensure that what we produce can be seen, heard and consumed by everyone and not just by bodies and minds that align with an arbitrary and exclusionary status quo? For me, the answer is as far as possible.

When we naturalize accessibility, we also naturalize disability, and tell disabled people and academics alike that they have a place in our gatherings, in our scholarship and in our communities.

**We have since made ASL interpretations of the English keynote speeches and LSQ interpretations of the French.

In Summary/Plain Language:

- Using lessons learned from our Between Ideals and Practices conference, this article highlights some ways academics and academic organizations can create more accessible conferences, content and spaces.

- Create an accessibility statement that communicates your organization’s accessibility goals

- To make your social media more accessible:

- Include image descriptions and alt-text on all visual media

- Offer captioning and transcripts for audio and video content

- Capitalize the first letter of every word on a hashtag

- Shorten links using websites like bit.ly

- Event tips to keep in mind:

- During registration, be sure to survey the access needs of presenters and attendees and provide speakers with guidance on creating accessible material

- Always offer attendees an option to attend events virtually and provide live captioning and ASL interpretation (if funding permits)

- Share an event accessibility guide that explains the location space, accessible entrances and washrooms and outlines access points in your event like American Sign Language interpretation, audio description or options for food sensitivities.

- Use plain language–a way to communicate in clear, straightforward and simple terms–to share academic information or offer definitions/explanations of jargon.

- Some lessons learned:

- Make sure to account for accessibility when creating your budget—research estimates for ASL interpreters, CART services and accessibility engineers/coordinators when applying for funds or grants

- Accessibility is a never-ending process that needs community support to work.